The Scourge of the Montage

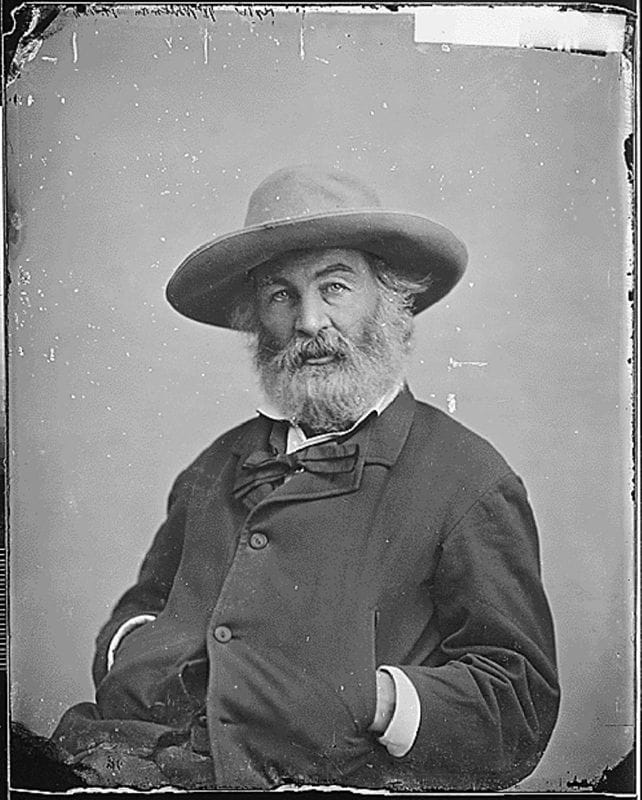

Over 150 years have passed since Walt Whitman told us that he contains multitudes. Presumably, so do the rest of us. College applications…

Over 150 years have passed since Walt Whitman told us that he contains multitudes. Presumably, so do the rest of us. College applications are both wonderful and maddening because they afford applicants the opportunity to talk about some of those multitudes — not just one, not just two, but potentially many, depending on how they use the applications. The applicants whose multitudes are most interesting and most impressive get in, and that’s fine.

A prevalent trend over the past few years — especially this year — has been to try to cram two, or more, of those multitudes at the same time and in the same application essay.

This type of essay is often called the “montage essay” or “braided essay,” referring to the idea that the topics are “woven” together throughout the essay, often in alternating paragraphs.

It’s appealing to want an essay to perform double, triple, or even quadruple duty. More is more, right? The prevalence of this approach, though, is inversely proportional to the difficulty of actually writing a good, honest essay.

A good montage essay identifies topics and zeroes in on their commonalities. The key is that the commonalities must be genuine.

For instance, an applicant might write about hiking in the mountains and studying geology — two different activities, but with a clear connection. Another might write about leading the debate club and the peer mentoring group, crafting a reasonable contrast between the clash of debate and the supportiveness of peer mentoring. A student who loves Huck Finn might write about her own trip down the Mississippi. More subtle montages can succeed when an applicant presents seemingly disparate topics but delights the reader with unexpected, convincing, and surprisingly meaningful connections.

What happens more often is that students arbitrarily choose topics that, in reality, have absolutely nothing to do with each other. They often invent a “theme” that supposedly unites these topics — and that’s where the montage almost invariably falls apart.

The “themes” that students concoct to connect topics tend to be hopelessly vague. I see things like “listening,” “noticing,” “entropy,” “voice,” “hands,” “notebooks,” “language,” “helping,” “collaboration,” or some other disingenuously “gee whizz!” idea that wants to be profound but is in fact stilted and banal. Everybody listens, collaborates, speaks, or helps; everything is subject to entropy — and every reader understands these concepts without needing a high schooler to explain them.

Often, these themes are metaphorical, meaning that they do not exist. Metaphors are literary devices, not expressions of reality. they don’t work in college essays because college applicants are not fictional.

Montage essays use themes because they’re broad, and therefore flexible, not because they’re genuine. But, because they’re so broad, it becomes painfully obvious when the topics don’t actually belong in the same essay together. A montage essay is like trying to dance ballet and play basketball at the same time. I suppose you can try, but why?

Ultimately, montage essays end up being overwrought, overthought, and too cute by half.

With this approach, themes end up predominating, and the rest of the essay simply serves the theme. The tail ends up wagging the dog. Instead of sharing genuine, authentic thoughts about an accomplishment, activity, or relationship, students obscure their true feelings by assigning a theme to them and watching it play out. This renders the application essay a rhetorical exercise rather than a genuine instance of self-expression.

This approach is likely inspired by certain English assignments, especially in AP English Language. The compare-and-contrast essay is a venerable form, testing how astutely, or creatively, students can find similarities or poignant differences between two pieces of literature. That’s a fine academic exercise when there’s a rubric and a grade and no one cares what you’re actually saying.

The disingenuous montage contradicts everything colleges claim to want.

Whatever you say about admissions offices, they always insist they want to get to know the “authentic” student. They want to know about students’ academic interests, extracurricular activities, family background, and all the rest. Each of these categories lend themselves to essays. I can promise almost everyone: students do not go about their day thinking about how their approach to math and pottery are both “expressions of creativity.”

Rather than revealing different important elements of a student, the montage ends up minimizing, obscuring, and trivializing them. It’s also vastly harder to write. An honest essay on a focused topic is always going to be not just better, but easier, than a dishonest essay that stretches to combine unrelated topics and ends up reading like two kids in a trenchcoat pretending to be an adult.

If you still think the montage is ideal, look at the prompts.

Of the seven prompts, six of them explicitly refer to single topics:

…a background, identity, interest; a time when; something…; an accomplishment; a topic…

№7 says “write whatever you want,” which certainly allows a montage. But not a single one — and not a single supplemental prompt I’ve ever seen — says, “Pick two different things, cram them together, and rhetorically justify why they’re side by side.”

In short: write about one thing. Write about it well. Write about it in detail. Write about it thoughtfully. Write about it sincerely.

The “montage” arises from a common misconception: that all elements of an application have to revolve around a theme, be “coherent” or “tie back to each other.” That’s nonsense.

If a student does ten different things, learns from them, and enjoys them, we don’t need to explain how they fit together. We don’t need to pretend they do. We can present them as they are, and colleges can, too. Colleges know and expect that interesting, accomplished people do different things, and for different reasons. They also know when a student is, though a contrived essay, conveying one facet of his personality over all others: insincerity.

The personal statement does not need to be all things to all people. From a purely pragmatic standpoint, if you use up multiple topics in your personal statement, you eliminate opportunities to revisit them elsewhere.

The best way to present multiple facets is to recognize that, for many colleges (including the most selective colleges), ”the application” is far more vast than “the essay.” Colleges require supplemental essays, and the Common Application includes optional pieces such as Additional Information and “Challenges and Circumstances.” Most applications require three recommendation letters, one from the school counselor and two from teachers. Many colleges accept optional letters. Each of these pieces enables students to present different facets and to give each facet its due attention.

Now, there may be instances where the montage is useful. For more active, accomplished students, any single topic can sustain a rich essay. Others might not have that experience or confidence, and they may struggle to fill 650 words on one subject. For them, a montage might help. They can introduce another topic to reveal something otherwise impossible to express. It might also make sense for a student applying only to colleges without supplemental essays — since students applying to selective schools often write three, four, or five essays per institution.

So, let’s go back to Walt. He doesn’t qualify or explain his “multitudes”, and it doesn’t drown them some syrupy “theme.” He celebrates them. We should celebrate them, too. Separately.

Postscript: Pro Westling and Essay-Writing

As I was drafting this post, I happened to hear an interview between Terry Gross and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson on Fresh Air. The Rock is eloquent — far more so than you might expect from a wrestler — which explains much of his success in acting. He talked about a key facet of professional wrestling: the gimmick.

Every pro wrestler has a gimmick they put on display in the ring, and sometimes outside of it. In Yiddish, they’d call this a shtick; in literature class, we’d call it a persona. Whatever the case, the gimmick is a character — or set of characteristics — that wrestlers graft onto their real personalities, and onto their physiques, for dramatic and entertainment effect.

Some gimmicks are more pronounced than others. But, The Rock acknowledged that a gimmick is a gimmick — and what the wrestler does in the ring is not necessarily who they are in physique.

The montage — or, rather, the theme that unites a given montage — is the gimmick of college applications. It obscures the real person for the sake of a persona. At least the artifice of wrestling is honest. That’s why I’d rather watch Sergeant Slaughter break a chair over André the Giant’s head than read an essay about how raising tropical fish and studying healthcare economics are basically the same thing.

Image credit: Walt Whitman Archive.